- Latest NewsUp-to-date articles giving you information on best practice and policy changes.

- Skills AuditsEvaluate your skills and knowledge, identify gaps and determine training needs.

Resilience: having it, losing it and teaching it

Adele Bates unpicks resilience and what we can do to inculcate it in ourselves, our pupils and in the classroom

Put your hand up if you’ve got resilience sorted.

It’s doubtful. So before we embark on an investigation of how we can support, create or adapt for resilience with our pupils or in our schools I want to hand out a permission slip:

No matter what you do around building your own resilience, there will be moments/days/weeks where it feels you have lost it completely.

That is OK.

That does not mean everything is hopeless, or you will never retain it again; strategies for sustaining resilience can help us to maintain it for longer periods of time and for a wider scope of pupils – we can turn the weeks of despair into days or moments, rather than letting it grow into years…

This article outlines some strategies to resilience that can be used in practice.

Teacher resilience

Pupil resilience begins with resilient teachers – in the same way that we cannot help pupils regulate their behaviour if we cannot regulate ourselves. Resilience is a practice that we dance with every day, not a post that we pass and tick off.

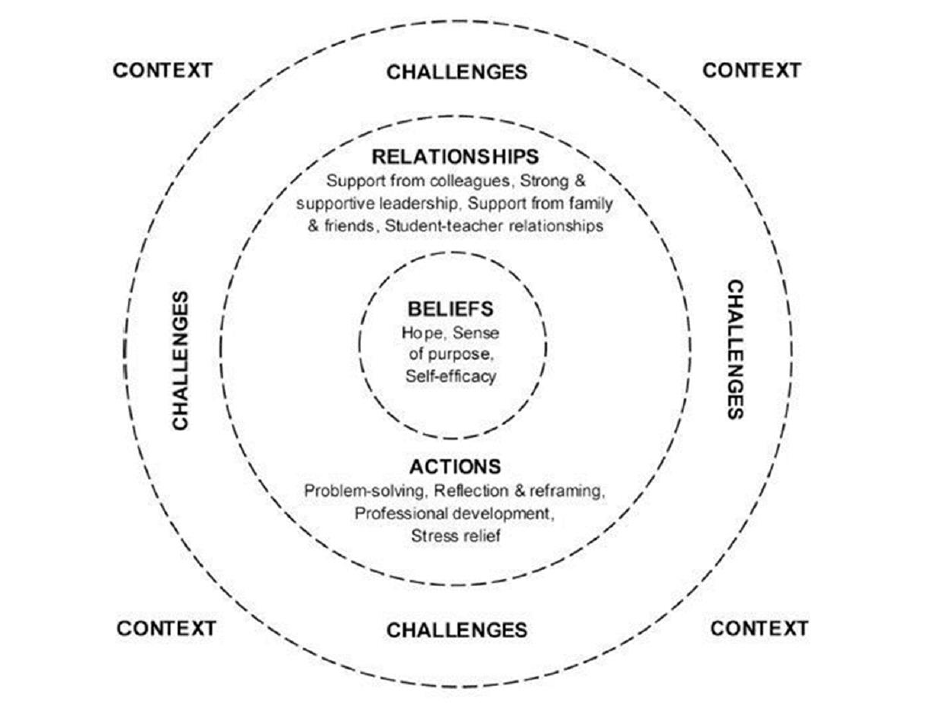

Greenfield’s resilience model (2015) makes it clear that resilience isn’t something that exists on its own. There are a number of factors that influence how resilient we can be, including:

- our context at any one moment

- the challenges we face

- our relationships (and how supportive they are)

- our actions in releasing stress

- our core beliefs.

The teacher who has just experienced racial discrimination from pupils before stepping into a meeting about asking for extra budget with their head, will need greater resilience than the one who has not. The headteacher who has had a negative spread in the local media about the new behaviour policy will need extra resilience as they go into the next governors’ meeting.

While this makes sense, the flaw in our society’s system is that we very rarely recognise this – we are not all starting from the same place when it comes to resilience, and we are all ever-changing.

Pupil resilience

Context

To return to the Greenfield model, let’s start with ‘context’.

A pupil’s context both outside of and inside of your (virtual or physical) classroom will impact how resilient they need to be just to access your lesson. If in a virtual space, one pupil may feel embarrassed of their home for a reason that means they don’t want to turn their camera on in your lesson. When you bring in a new concept around chemical equation theory, this pupil will need extra resilience and self-regulation to help them focus on the task and new information.

Challenges

Moving to the ‘challenges’ part of the model, I give you a simple example. During my NQT year I took a group of 20 children on a camping trip. I was the only teacher there – everyone else was a part of the Wildlife Trust, teaching the pupils how to make fires and whittle. At night, as we bunked down in the barn, it was fascinating to watch how the pupils reacting differently to sleeping on a concrete floor in a sleeping bag next to their classmates (and enemies). It was obvious which ones were involved in Duke of Edinburgh and were used to such conditions – they just got on with it.

When we encounter new challenges, we require more resilience; when a challenge is familiar to us, we have a wider capacity to overcome the challenge – we have more resilience.

Some pupils, when faced with the unknown, found strategies to deal with it – they used the ‘relationships’ part of the model and asked friends for advice or help.

Having a supportive network around us builds our resilience. This situation may be new and scary to me, but the fact that it’s not for you, a person I trust, strengthens my belief in myself to do this.

Now imagine the pupil who beds down for the first time away from home and does not have any friends in this group that they trust. How much more resilient are they required to be when they see a bat for the very first time in the room they’re sleeping in?

Actions

Next, I was interested to find some of the more seemingly lively, confident pupils turn to me worried – ‘Miss, when should I clean my teeth?’ All the pupils were 13 years and over. I wrongly assumed that they wouldn’t need me for these types of tasks or decisions, and I suspect that if in their usual homes (context) then they wouldn’t either.

However, the different environment and people surrounding them meant that they needed more support. They had a problem, they felt confused and they found a strategy that would help them – ask the teacher.

I would guess too, that in this moment they felt the need for some stress relief. When I asked ‘well, when do you usually clean your teeth?’ a pupil told me that his mum tells him when to do it. Asking me – in loco parentis – was the next best thing to sooth his worries. He found the ‘action’ from the model that would help him.

Beliefs

Finally, I am interested in the pupils who didn’t feel they could attend the trip – the ones who did not feel comfortable being away from home sleeping in a barn. This brings us to ‘beliefs’: these pupils (or possibly their parents or carers) did not believe that this experience was for them, either they were not ready, it was not suitable or they were too scared.

In contrast, despite the fears that some of the pupils clearly had about the experience, they had patterns of self-belief, of self-resilience, that enabled them to try new things that felt scary and trust that they would survive.

Support and presence

Psychologist, author and father Dr Daniel J Siegel gives this definition of resilience.

Resilience means being flexible and strong in the face of stress, and it is what we need to approach any of the challenges of life and rise above adversity, learn from the experience and move on with vitality and passion. (Siegel, 2014)

He emphasises that our ability to have a resilient mind rests on how supported we feel. For our pupils with unsafe homelives or adults in their lives who are unable to care for them, the lack of support will directly affect how resilient the child can be in your classroom.

An example: you asked everyone to read a sentence of the class novel you’re reading. Nearly all the pupils comply; one pupil, however, lashes out, it is too much for her – she does not feel secure in the task, and she does not have the experience of being supported with new tasks. She does not feel safe, and so her resilience is smaller.

Siegel also teaches us that ‘presence enables us to develop resilience’.

If we are present to the fact that we have difficult surroundings, we are facing challenges, we need help – then we are able to access support that can help us. Or, if we recognise that in a particular situation or moment that we have a balance of what we need, if we are present we may realise we are able to help others.

Recovery and growth

Adrienne Maree Brown, a black, queer woman, social justice facilitator, healer, doula and author, examines resilience in her book Emergent Strategy: shaping change, changing worlds. She describes resilience as ‘how we recover and transform’ (Brown, 2017). She uses the model of nature to encourage us to understand that resilience is something necessary and beautiful for our growth.

Nothing in nature is disposable. Part of the resilience of nature is that nothing is wasted… Humans have made of ourselves a hierarchy of value in which some people are disposable. (Brown, 2017)

She goes on to explain that our societies mean that some humans can ‘fail’ – and be put away – tortured, imprisoned – put in an isolation booth? Put on permanent exclusion?

To bring her observations and nature model of resilience into the school setting, we must ask the questions: how can we view ‘wasteful’ parts of a lesson as a chance for us to strengthen ours and our pupils’ resilience? When pupils disrupt our teaching and ‘waste’ our time – what does that teach us about our own and their resilience? How can we transform this to improve and evolve for everyone’s learning?

How can we support resilience in the classroom?

- Know that not all of your pupils will have the same level of resilience.

- Realise that whilst pupils may have a great resilience for some tasks, they may not have for others, or they may have resilience when working with a teacher they have a positive relationship with and struggle with others.

- Differentiate your learning opportunities to account for difference. For example, some pupils may need to read in pairs first before reading out loud to the whole class. In the same way you would scaffold a poetry analysis, scaffold resilience – allow pupils to know that they are safe and then invite them to take the next step.

- Understand that a lack of resilience – a feeling of not being safe – may come out through behaviour that challenges you. Find out why that behaviour is happening before punishing.

- Include mindful, presence-bringing activities into your lesson. Help pupils notice when they feel good, what that feels like, when they don’t and provide tools for them to help themselves.

- Find opportunities to learn from ‘wasteful’ or ‘bad’ moments in a lesson. Does a chatty, unfocused lesson teach us that pupils would benefit from a calming, focusing starter activity after lunch? Or does a fight between two pupils reveal to us the lack of inclusion and sense of belonging in our school?

Last Updated:

02 Mar 2021