- Latest NewsUp-to-date articles giving you information on best practice and policy changes.

- Skills AuditsEvaluate your skills and knowledge, identify gaps and determine training needs.

Understanding sensory processing disorder

Is a child misbehaving or are they displaying a self-regulatory behaviour? Gill Barrett discusses these issues in relation to her school's practice

Key definitions

- Behaviour – the way a person acts in response to a particular situation or stimulus.

- Sensory processing – the way the nervous system receives messages from the senses and turns them into responses.

- Restrictive behaviour – one that limits a person’s life opportunities to access their environment and community fully.

- Hyposensitive – the body requiries high levels of stimulation due to an under-responsive response.

- Hypersensitive – the body is highly alert and responsive to sensory stimulation, wanting to block out sensory input.

'When he starts to behave, then he can have his sensory break.'

These words still echo around my head, words overheard during a placement assessment at a school.

The misconception was that this child's 'misbehaviour' was because he was being ‘naughty’, and not that he was trying to regulate himself so that he didn't have a total meltdown. The difficulty is, how can we tell the difference between ‘naughtiness’ and sensory need?

What is sensory processing disorder?

For a child with sensory processing disorder (SPD), sensory information goes into the brain but becomes mixed up and the resulting responses are not always socially acceptable.

One way of understanding the wiring in the brain is to think of a new ball of wool, with the threads neatly lined up. If these were neurons the messages would pass along easily, with responses being well learnt and appropriate.

The key to understanding whether a behaviour is a learnt behaviour or a sensory processing need is to assume that it is sensory

A child with SPD (and frequently autism) has a brain where the ball of wool has become tangled and twisted and the paths for the messages can no longer be easily traced. Messages struggle to pass along, resulting in mixed messages and muddled responses. The sensory input then becomes misinterpreted and the child’s body goes into a ‘fight’ or ‘flight’ reaction.

The resulting behaviours can act as a self-regulating response. They may be deemed inappropriate within society but to the child the behaviour has prevented their total meltdown. Stopping this sensory need behaviour without meeting its purpose can easily result in more challenging behaviours being displayed.

Signs of SPD

| Sensory system | What it controls | Behaviours that show dysfunction within the system |

| Vestibular | Co-ordinating movements, balance, eye movement and spatial orientation. | Rocking, jumping, teeth grinding, pacing, throwing self onto the floor, spinning, head banging, ear flicking, humming. |

| Proprioceptive | Body’s ability to know its own position in space, e.g. knowing that your feet are touching the grass. | Running, jumping, throwing self onto the floor, head banging, shaking fingers, hitting self, pinching, biting, over focusing with their eyes. Watching hands or feet as they move them. |

|

Somatosensory (tactile proprioceptive) |

The ability to interpret bodily sensation. Sensation takes several forms, including touch, pressure, vibration, temperature, itch and pain. | Biting, mouthing objects, pica, picking skin or eyelashes, need for constant touching, crashing into things. Dislikes wearing shoes or clothes. |

| Gustatory | Taste | Picky eater, difficulty eating mixture of textures, flavours or colours. Wanting food very hot or cold. Frequent drooling, dislikes brushing their teeth. Licks, chews, or mouths inedible objects frequently. |

| Auditory | Sound | Shrieking, tooth grinding, vocal play, ear flicking and humming. |

| Visual | Sight | Love of bright or moving lights and colours. Watching moving pictures. Wanting to wear sunglasses. Hiding their eyes. |

| Olfactory | Smell | Sniffing things, greeting people by sniffing them. |

Problems with identification

Each child is an individual and with each sense the child could be hypersensitive or hyposensitive.

The warning signs of each sensory processing need can overlap, making clear identification even more difficult. A child could also be both hypersensitive to one sense while being hyposensitive to another.

Added to the behaviours linked to their sensory processing system they will also have learnt behaviours being displayed. Unpicking all these behaviours can appear impossible.

The key to moving forward

At The Loddon School, we assume that:

- every child has a high sensory need

- all behaviours serve a function of getting the child’s needs met.

In response to these two assumptions we offer:

- identification and assessment of restrictive behaviour

- continuous behaviour assessment using a blended therapies approach (psychologist, occupational therapist and speech and language therapist working together)

- a fully structured curriculum that offers continuous sensory regulation.

Identifying and assessing restrictive behaviours

When assessing a child, one restrictive behaviour is identified and focused upon.

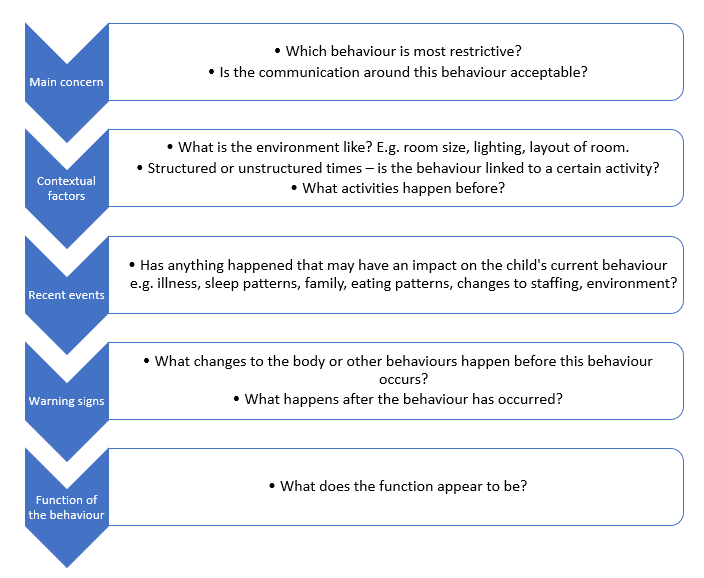

The chart below shows the structure of the observation and monitoring period. Discussions with key members of staff provide the required information.

Case study example

- Main restrictive behaviour – Adam will regurgitate small amounts of food or liquid (with no apparent physical cause) on a regular basis.

- Contextual factors – he appears to recognise this sensory need but cannot request or communicate this need to others.

- Warning signs – Adam displays an increased level of anxiety, pacing and rocking. He demands lots of sensory activities that are calming, but this does include regurgitating. There is an increase of him putting a lot of food in his mouth and eating his food really quickly. There is an increase in pica behaviour.

- Function of the behaviour – Adam has an under-responsive sensory system. He is particularly seeking sensory input in his mouth which is why he is potentially regurgitating. Pica behaviour is likely to be linked to trying to obtain that sensory feedback in his mouth.

Recommendations

- Trial Z-vibe for proprioceptive input into the lips, tongue, cheeks, gums and jaw. This sensory feedback can help to wake up the mouth and increase oral awareness, calming the nervous system. Using it in front of a mirror will increase the visual feedback and integrate the visual and tactile senses.

- Increase structured messy sensory play – texture, smell, touch (e.g. tapioca, semolina, rice pudding).

Strategies at a whole-school level

- The key to understanding whether a behaviour is a learnt behaviour or a sensory processing need is to assume that it is sensory.

- Structuring the whole school day so that it modifies arousal levels for everyone and maintains optimal levels of arousal (what we call being ‘alertly calm’) will ensure that the child is in the best place to learn, to be engaged and therefore reduce the need for more challenging behaviours to be displayed.

- There is an overriding need to use sensory activity before the behaviours start otherwise this re-enforces the negative behaviours you wish to reduce.

- Having a sensory diet which is totally integrated into each child’s timetable allows sensory integration to treat the underlying cause of the unwanted behaviours.

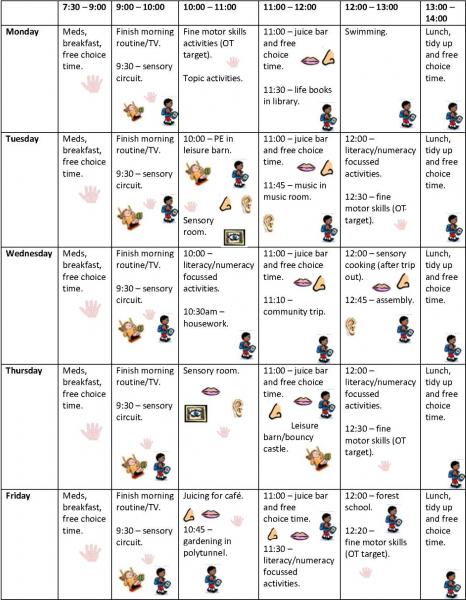

Individual timetables (morning)

Each child has a timetable built around their preferred learning and their sensory diet.

The symbols within each time slot emphasises the sensory diet aspect that needs to be met either by the major learning activity or with an additional sensory activity input provided. This could be that the child walks via the swings to their next activity and stops for a five-minute swing – a routine which will mean that the child can finish the activity knowing the regularity of these sensory inputs.

Careful hourly monitoring of behaviour and sensory input patterns will show staff the difference between behaviours when the sensory need has been met and those that are sensory led. Having a school structure that places sensory awareness as a consistent focus for all staff and having a good understanding of the behaviour profiles moves practice forward rapidly.

Key takeaways

- Think ‘sensory need’ first!

- Structure the day so no child reaches a point when their sensory system is out of balance.

- Remember that behaviours are serving a purpose to the body or personality of the individual child.

Further reading

- Personalised learning for life using supporting strategies (PLLUSS)

- Caldwell, P. and Horwood, J. Using Intensive Interaction and Sensory Integration with people with severe autism. Handbook for working with intensive interaction (2008)

- Biel, L and Peske, N. Raising a sensory Smart Child. The Definitive Handbook for helping your child with sensory processing issues (2018)

Last Updated:

09 Dec 2019