- Latest NewsUp-to-date articles giving you information on best practice and policy changes.

- Skills AuditsEvaluate your skills and knowledge, identify gaps and determine training needs.

Addressing the roots of behaviour: case study and sample plan

Recognising the needs behind poor behaviour can minimise disruption and improve classroom engagement. Ruchi Sabharwal explains how you can differentiate your school's strategies for better behaviour

Differentiated behaviour strategies

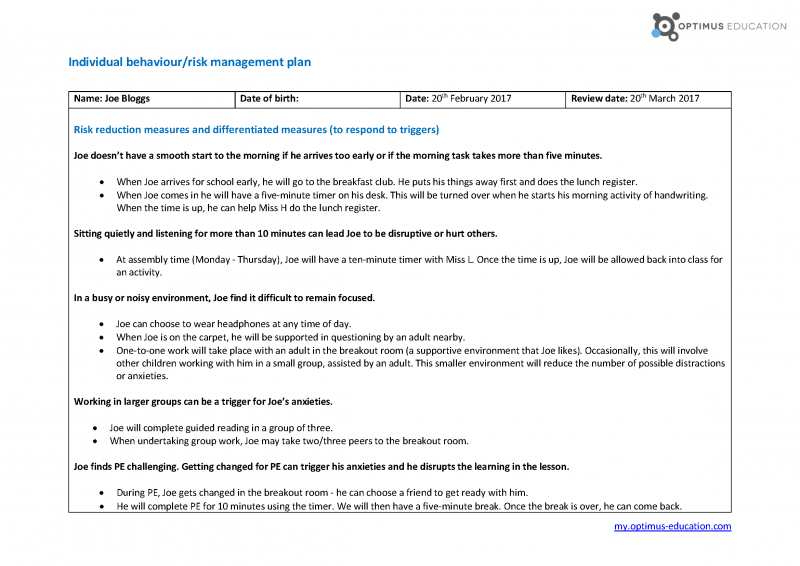

Download Ruchi's sample individual behaviour plan (IBP) to set out your strategies for responding to different levels of behaviour, from risk reduction to post-incident recovery.

The Weatheralls Primary School is based in East Cambridgeshire with approximately 620 children on roll. The children primarily come from a white British background, with an above average level of children eligible for pupil premium funding and registered with SEND.

The school has a simple behaviour management system based on positive rewards and sanctions for misconduct, and includes a ‘traffic light system’ of a verbal warning, yellow card and, if the behaviour is not modified, a red card.

Children who receive a red card are sent to the senior leadership team and miss 15 minutes of their lunchtime as a consequence.

While this longstanding system has the desired effect for the majority of children, we noticed that the system had no impact (and in some cases a negative impact) on a handful of children exhibiting anti-social behaviour.

As we approached the end of the first term, the frequency and types of behaviour for a minority of pupils had escalated and the perception held by staff was that behaviour in the school had ‘gone downhill'.

The perception held by staff was that behaviour in the school had ‘gone downhill'

In order to devise an effective strategy for supporting these pupils and staff, we logged incidents of misbehaviour and the impact.

Through this exercise, we realised that each incident negatively impacted multiple staff members and pupils, and that staff were repeatedly taking the same responses, such as calling for SLT backup. It was vital that we developed a whole-school approach to dealing with extreme behaviour.

| Behaviour | Effect |

|---|---|

| Refusal to work | Pupils refusing to engage with specific tasks would disrupt the rest of the class. |

| Defiance | When pupils were disrespectful or defiant, some adults were not well-equipped to deal with this and sometimes escalated the situation. |

| Walking out of lessons |

Pupils who could not manage themselves in class were walking out, roaming the school building and grounds. Teachers without TAs were not able to leave the classroom so senior management were regularly called to deal with these children. |

| Running away | The natural instinct of ‘fight or flight’ would kick in and pupils would run away from any adult interaction. In some extreme cases, attempt to leave the school premises. |

| Violence |

In the most extreme cases, where pupils felt a heightened state of anxiety, stress and loss of control, they communicated this through anger. Peers and adults were physically hurt at times. This led to parental concerns and complaints and impacted on staff morale. |

We also identified that, despite perceptions, there were only four or five children who struggled to maintain self-control in the classroom and communicated this through their behaviour.

Senior leaders were constantly being called to deal with pupils who were taking themselves out of class or having regular ‘meltdowns’, leaving the teacher unable to teach or having to escort the rest of the class to a safe area.

In short, teachers needed to get back to teaching, pupils back to learning and leaders back to driving school improvement.

Rethinking behaviour

Our first action was to look at staff perceptions of ‘bad behaviour’. We encouraged teachers and teaching assistants/learning support assistants (LSAs) to consider the quality of teaching and continually reflect on behaviour in lessons.

- What is the behaviour? (Is it less serious, more serious or extreme?)

- Is the behaviour difficult or dangerous?

- What is going on for that child? (What is the underlying cause?)

- Is the work right?

- When does the negative behaviour happen? (What does this communicate?)

- Does the child feel safe? (Are there any attachment needs or communication barriers?)

Staff used tables such as the one below to identify the type of support a pupil needs.

| Name | Year | Pupil Premium/SEN/Confirmed diagnosis? | Nature of concern | How are you currently managing the behaviour? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Our ethos for behaviour needed to address the social, emotional and educational barriers some of our pupils face, with attachment disorders playing a huge role.

Staff could no longer expect all pupils to conform, or pine for the ‘good old days’ when behaviour was perfect and no thought was given to the root causes.

Punitive consequences simply do not work with children as they once did.

Our school's values

- A shared focus on inclusion of all pupils.

- A shared set of values and beliefs.

- Open and shared communication.

- A shared commitment to diversion and de-escalation.

- A shared responsibility for risk management.

- A shared responsibility for the reparation, reflection and restoration of behaviour.

- A shared belief that positive experiences leads to positive experiences and pro-social behaviour.

We knew we had to work towards a positive, therapeutic system, and that whole-school buy-in was vital if our move towards a ‘small garden’ nurture room was to prove successful. The DfE guidance, 'Mental health and behaviour in schools', was invaluable.

To further our staff’s understanding, we invested in whole-school training. This prioritised:

- de-escalation

- ASD

- restorative behaviour

- attachment needs

- mental health needs.

We discussed strategies for ‘managing in the moment’ and added less serious de-escalation strategies to our behaviour policy.

- First and foremost, disempower the behaviour by ignoring it or not appearing bothered. If the child is under a table, say: ‘Sit on the carpet here or the carpet here?’ If still no response, ignore or say: ‘You can listen from there.’

- Try an ‘antiseptic bounce’. Remove the pupil from potential triggers or an ‘audience’ by sending them to another place to work or giving them a task.

- If the child is getting cross, validate their feelings but stick to the broken record. Do not start a ‘battle’: ‘I can see that you are frustrated, but I need you to…’

Approaching behaviour with this broader range of techniques, staff can more confidently preempt situations before they arise.

For example, we have a pupil in Year 4 who would regularly shout out, follow the teacher around the classroom, create chaos and demand attention from their peers. Before functional behaviour training, staff would’ve addressed this behaviour by simply ignoring it, or threatening consequences that had no long-term benefit.

Having recognised that the pupil has anxious attachment, we now make a point of acknowledging them first in most classroom interactions

Having recognised that the pupil has anxious attachment, we now make a point of acknowledging them first in most classroom interactions – this addresses the pupil’s demand to be noticed. She is positioned towards the back of the classroom, where she can see everything and feel secure.

If she does have an outburst, staff acknowledge the emotion first in order to validate it, but quickly bring her back by repeating the instruction. We share a joke or use humour as an early intervention when we can tell the pupil is about to ‘have a wobble’, which has significantly reduced the number of disruptions (and sanctions).

Simply put, we differentiate behaviour management in the same way as learning.

The small garden

Despite our investment in staff training, a minority of children continued to struggle with behaviour management in lessons. These children were identified as having ASD, attachment disorders or mental health issues. External support was virtually non-existent.

In the interest of pupil and staff wellbeing, we identified the need for an area in which children could reflect and rest safely if they were unable to manage in the classroom.

Our ‘small garden’ was quickly set up as a space for children to work in an environment of ‘care and control’, not punishment.

Our school's aims

- Reduce the number of angry and/or violent outbursts.

- Reduce the number of fixed term exclusions.

- Reduce the number of classroom exits.

- De-escalate before a crisis occurs.

- Reduce the risk of harm.

- Teach internal, rather than imposing external, discipline.

We are now two terms into our small garden approach and we have had small, but immediate successes. The children who were previously leaving the classroom, roaming the school, having a negative influence on their peers, missing out on learning and, more worryingly, feeling increasingly disaffected by school, now have a space to work and are given the opportunity to succeed.

A trained and experienced LSA has been integral to the success of the small garden, and we have seen a clear improvement in children’s engagement (and fewer fixed-term exclusions) as a result. And most importantly, teachers are back to teaching without disruption.

If you are deliberating the use of a safe space like ours in your school, be prepared to make mistakes and learn along the way. Success will come from communication with all stakeholders, including parents and the pupils themselves.

Be clear on the purpose of the room when explaining to these people: is it a ‘de-escalation’ space where children calm down, or is it a place to work? We’ve found that it can only be one or the other.

Is it a ‘de-escalation’ space where children calm down, or is it a place to work? We’ve found that it can only be one or the other

These spaces can be great opportunities for outdoor or creative learning, moderated by clearly-set ground rules. But be wary of grouping all children with behaviour issues in the same space at the same time. Don’t be afraid to create individual timetables for pupils who need them – allow pupils to flourish, not fail.

If teachers feel that general classroom management and support is insufficient, and negative behaviour is on the rise, senior leaders need to know about it.

Together, they should keep one overarching question in mind: ‘How are we differentiating the day for this particular pupil?’

Priorities for better behaviour

- Identify the pupils that need individual behaviour plans (IBP). This should be no more than two per cent on average. If it is higher, consider whether you are being over-cautious.

- Support teachers with their general classroom management to avoid ‘copycat’ behaviours.

- Talk to pupils and teachers about levels of anxiety throughout the day. Your observations should note time of day, adult, lesson, seating and so on. Use this information to inform the IBP.

- Keep the IBP very tight, with a breakdown of the day. Include time, adult, location so that it becomes a cribsheet for the adult working with the pupil. Build in positive experiences to help pupils flourish. Include ‘extra-curricular’ activities to motivate and short learning tasks.

- Flag any concerns with the SENCO early on for better chance of external support.

- Meet with parents and pupil to discuss the IBP. Ensure the pupil is clear on the expectations and purpose of the plan.

- Share the plan with all stakeholders, including all teachers and TAs, not just the class teacher. It’s crucial that adults do not unnecessarily challenge one another, so sharing really is caring!

- If the pupil does not have an adult, assign them a mentor for regular ‘check-ins’ to promote positive relationships outside the classroom.

- Focus on inclusion, respect and empathy. Adults understand not to take anything personally and to start each day with a new slate.

Download and adapt a sample individual behaviour plan to set out your strategies for responding to different levels of behaviour, from risk reduction to post-incident recovery.

Ask yourself, ‘Is what you’re facing a school-wide crisis, or a handful of individuals who need additional support or risk reduction plans?’ Only a caring, consistent and collaborative approach to behaviour will succeed in either case.

Whatever approach you take or techniques you use, remember that every child, regardless of their behaviour, has the right to an education.

Last Updated:

08 Jun 2018