- Latest NewsUp-to-date articles giving you information on best practice and policy changes.

- Skills AuditsEvaluate your skills and knowledge, identify gaps and determine training needs.

Evidence based teaching: five strategies and how to use them

What does research tell us about effective teaching? Put theory into practice with these five ways to draw on educational research

What works in education? Often the disconnect between theory and practice means that, as Tom Bennett has put it, popular beliefs often linger on ‘long after they have been shown to have little or no evidence base.’

Here I’ll focus on some ideas about what works and why, linking to the research that supports it. You can read more on what doesn't work on my accompanying myth-busting blog.

1. Memorable explanation

‘Chalk and talk’ teaching has gained a bad reputation, but effective explanation is key to understanding. In Why Don’t Students Like School cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham points out that stories are ‘psychologically privileged’ because their structure lends itself to comprehension and memory:

- stories make causal links

- stories tend to contain conflict

- stories contain complications

- stories are built around characters.

Willingham suggests that what makes stories so effective, is that you must think about the story’s meaning throughout. This thinking about meaning is excellent for memory.

How might you incorporate this into your teaching?

Think about how you use explanation memorably to convey meaning to pupils and encourage recall. Willingham points out that the best explanation is:

- interesting

- easy to understand, because pupils know the structure

- easy to remember, because it uses what Willingham calls the ‘Four Cs’: causality, conflict, complications and character.

Find out more on making ideas stick.

2. Build up knowledge

Knowledge has a ‘velcro’ effect. The more learners know, the easier they will find it to learn new information.

The Bloom’s Taxonomy description of knowledge as ‘lower-order’ can be unhelpful. In fact, knowledge is vital to ‘higher-order’ thinking. As Daniel Willingham says, ‘it makes no sense to try and teach critical thinking devoid of factual content.’

Our working memories are handicapped because they can only hold a relatively small amount of new information. Research by Renkl and Atkinson finds that the intrinsic load of learning is reduced when pupils have more prior knowledge; therefore the learning becomes easier.

This is because the limits of the working memory apply only to new information. Knowledge has a ‘velcro’ effect. The more learners know, the easier they will find it to learn new information.

How might you incorporate this into your teaching?

Consider how you are building up pupils’ knowledge base. Joe Kirby blogs about how Michaela School is using knowledge to support learners.

Find out more on how knowledge helps.

3. Use desirable difficulties

In recent years, the emphasis has been on rapid progress, but Professor Robert Bjork, points out that the teaching methods used to induce rapid progress often create a temporary illusion of fluency, and actually fail to support long-term learning.

Instead he suggests that teachers should build ‘desirable difficulties’ into their teaching, because learning is deeper and more permanent when it requires effort.

Desirable difficulties feel counter-intuitive because they slow down learning, but are actually more effective in ensuring that learning is transferred to the long-term memory.

|

Teaching methods for rapid progress, but poor retention |

Desirable difficulties leading to long-term learning |

| Learning tasks are predictable. | Learning tasks are varied. |

| The learner is supported by constant cues from the teacher. | Teacher feedback is delayed so the learner has to think for themself. |

| A topic is taught in a single block. | Different topics are interleaved. |

How might you incorporate this into your teaching?

Look at your curriculum planning. How are you interleaving topics and types of practice activity to introduce desirable difficulties?

Find out more on desirable difficulties, or watch the video below.

4. Order your activities

All learning places a cognitive load on the limited capacity of the working memory. The key is to choose activities that minimise this by contributing directly and efficiently to learning.

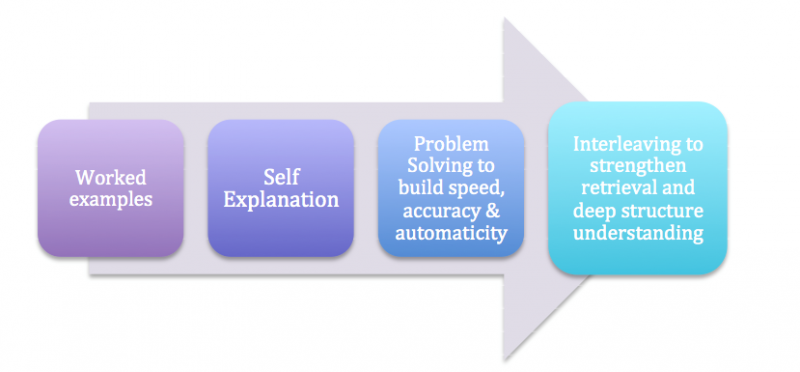

The order in which pupils do activities makes a difference. In their research into problem-based learning Kirschner, Sweller and Clark discuss the ‘expertise reversal’ effect.

When they are novices, learners learn more efficiently from worked examples; however as they gain expertise, problem-based activities promote higher performance.

Renkl and Atkinson’s research into cognitive load found that while pupils are learning, self-explanation is a valuable activity, helping them to understand and rationalise the process of the activity. As pupils become experts though the emphasis changes to speed, accuracy and automaticity.

How might you incorporate this into your teaching?

Consider the order of activities for pupils as they gain expertise.

Find out more on permanent learning.

5. Testing as learning

Testing can sometimes be seen as a summative process - something we do merely to measure learning.

In fact, research suggests that regular testing is an important formative element in the learning process because it slows down forgetting. For information to be permanently learned, it needs to be transferred from the working memory (where we process information) to the long-term memory (where information is stored).

Regular testing helps both to embed learning securely in the long-term memory, and strengthen pupils’ ability to retrieve the information. Research by Roediger, Putnam and Smith found ten benefits to regular testing.

- Retrieving information aids retention of learning.

- Testing identifies gaps in learning.

- Testing causes pupils to learn more from the next study episode.

- Testing improves pupils’ organisation of learning.

- Testing improves transfer of learning to new contexts.

- Testing can improve retrieval of learning that was not tested.

- Testing improves metacognitive monitoring.

- Testing prevents interference from prior learning when learning new material.

- Testing provides useful feedback to teachers.

- Frequent testing encourages pupils to study.

How might you incorporate this into your teaching?

Consider ways of introducing regular quizzing into lessons. Don’t forget to interleave questions to introduce ‘deliberate difficulty.’

What doesn't work?

Research is also telling us about what doesn't work for learning. See the accompanying blog Myths and Shibboleths: What doesn’t work and why?

Last Updated:

01 Feb 2018