- Latest NewsUp-to-date articles giving you information on best practice and policy changes.

- Model PoliciesA comprehensive set of templates for each statutory school policy and document.

- Skills AuditsEvaluate your skills and knowledge, identify gaps and determine training needs.

Archived Content

This page has been archived. It's no longer part of our core content, but is still available for users who want to access it

Working with Resource Allocation Systems: key components and characteristics

Anita Devi completes her series of articles looking at SEN commissioning and Outcomes Based Accountability by examining Resource Allocation Systems (RAS) in relation to the proposed personal budgets

What is RAS?

For individuals who need additional support, a Resource Allocation System provides a set of parameters or rules to be applied that allows fair allocation. In effect, RAS connects a particular level of need with a particular level of funding. This could be funding given directly to the setting or situations where young people or families have opted for a personal budget.

One of the challenges with the current SEN system is that in Statements need was initially equated to hours of support and thereby a level of funding, thus limiting the creative solutions possible to meet the need. Stating hours of support increases the cost factor, but not necessarily the impact. It is not sustainable long-term and does not build a culture of high aspirations and increasing independence. This is not a reflection on any individual, profession or role; sometimes the solution to meet a need isn’t about extra people, but about doing things differently or additionally. Hence the broad definition of special educational needs (draft SEN Code of Practice, DfE, Oct 2013 p10) ‘covers children and young people from 0-25 years of age, where a child or young person has a learning difficulty, disability or health condition which requires special educational provision to be made’.

New Horizons: 2014 and beyond

Stating hours of support increases the cost factor, but not necessarily the impact. It is not sustainable long-term and does not build a culture of high aspirations and increasing independence

The proposed SEND reforms under the Children and Families Bill will move us away from a system-centred approach to a person/family centred approach. The distinction in emphasis is significant, not necessarily in determining what we do, but how we do it.

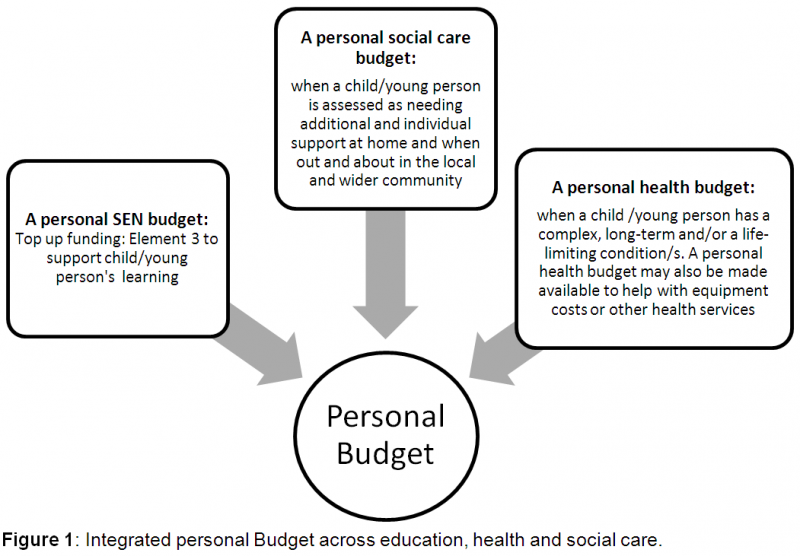

Under the proposed changes, ‘young people and parents of children who have Education Health Care (EHC) plans have the right to request a personal budget, which may contain elements of education, social care and health funding. Partners must set out their arrangements for agreeing personal budgets and should develop and agree a formal approach to making fair and equitable allocations of funding’ (draft SEN Code of Practice, DfE, Oct 2013 p40)

The holistic nature of an EHC plan covering the special education, health and care services should be reflected in the personal budget and vice versa. These should be based on clear and agreed outcomes. Issues such as clinical, safeguarding and learning governance can and should all be built into the EHC plan. The funding for a personal budget can come from education, health and social care (via a single integrated fund stream) and the scope of that budget will vary depending on the needs of the individual as well as the eligibility criteria for the different components and the mechanism for delivering the services required. So invariably the process is about defining need, the level of associated support required (across services) and the associated budget for the defined level of provision. Local circumstances, commissioning arrangements and the type of school the parents (or the young person) request will also be taken into account when setting a personal budget.

Once allocated with a personal budget the young person, family or broker acting on behalf of the family will need to consider commissioning the relevant services. The SE7 Framework for Choice and Control provides a good model around the quadrants for personalisation; which can support this process.

Components and characteristics of RAS

A resource allocation system, therefore, with regard to personal budgets, should provide a transparent and participative approach for identifying what additional and individual provision is available across education, health and social care

The charity In Control (February 2013) defines three common components of all RAS:

- Budget: the funding identified by a funding agency to support a group of children or young people who share a broad set of linked support needs

- Eligibility: A clear explanation of what makes a child, young person or family eligible for funding from this budget

- Purpose: A clear statement of the outcomes which this funding must support the delivery of, by meeting support needs identified through the assessment process.

A resource allocation system, therefore, with regard to personal budgets, should provide a transparent and participative approach for identifying what additional and individual provision is available across education, health and social care. With personal budgets becoming an option for SEN, health and social care, there will need to be a framework and agreement in place which outlines how the funding can be integrated ‘around a child’. By default this implies a joined-up assessment process and an EHC plan supported by a joined-up approach to allocating a single budget. The ‘real’ wealth a family brings to any circumstance will also need to be taken into account when allocating a personal budget.

Why use RAS?

In 2012, Simon Duffy, Director of The Centre for Welfare Reform defined seven principles that underpin RAS:

- Empowering

- Creative

- Sufficient

- Equitable

- Sustainable

- Transparent

- Efficient

The 3 underpinning principles of the draft Code of Practice

The draft SEN Code of Practice (DfE, Oct 2013) distinguishes between principles underpinning the code (p12) and principles in practice (page 13). The three underpinning principles of the draft SEN Code of Practice are set out in Clause 19 of the Children and Families Bill. Local authorities, in carrying out their functions under the Bill, must have regard to:

- the views, wishes and feelings of the child or young person, and their parents;

- the importance of the child or young person, and their parents, participating as fully as possible in decisions; and being provided with the information and support necessary to enable participation in those decisions;

- the need to support the child or young person, and their parents, in order to facilitate the development of the child or young person and to help them achieve the best possible educational and other outcomes, preparing them effectively for adulthood.

These could be shortened to:

- Participation

- Transparency

- Preparation for adulthood.

The principles in practice of the draft Code align more to Simon Duffy’s model (written in italics), as they specifically state:

- Involving children, parents and young people in decision making (empowering)

- Identifying children and young people’s needs (equitable & transparent)

- Greater choice and control for parents and young people over their support (equitable & sustainable)

- Collaboration between education, health and social care services to provide support (transparent, creative, sustainable)

- High quality provision to meet the needs of children and young people with SEN (creative, efficient, sufficient & sustainable)

- Supporting successful preparation for adulthood (empowering, creative, sustainable)

In effect a well designed RAS enables practitioners (at all levels) to implement the principles in practice of the draft SEN Code of Practice through a real and open dialogue with children, young people and their families. Decision making criteria is transparent, unlike many panel decisions under the current system and there is an shared understanding of fairness and consistency.

How does RAS work in practice?

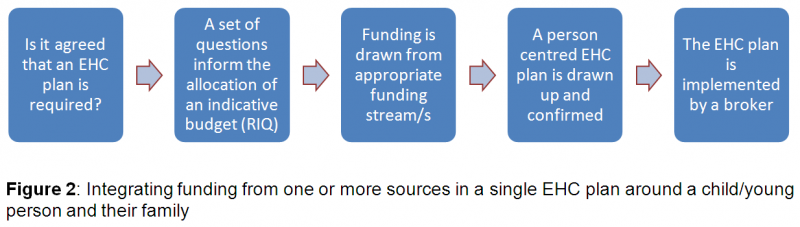

A framework process is required to underpin any such system. In 2013, Wigan Local Authority developed the Resource Indication Questionnaire (RIQ) to support the integration of funding from one or more sources into a single EHC plan. The process was subsequently defined as follows:

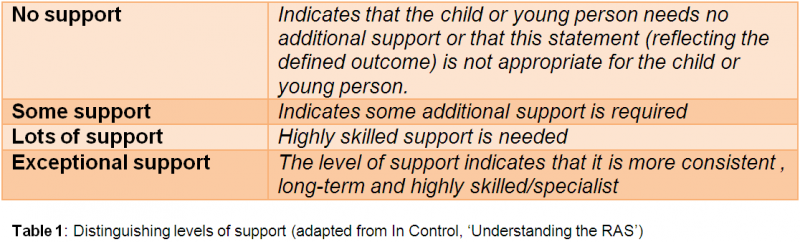

The questions included in a resource allocation questionnaire like Wigan’s focus on a locally defined set of outcomes/aspirations. Against each outcome, a Likert –type scale is defined to determine the level of support.

In RAS, against each level of required support, a range of points and associated funding is defined. Completion over the whole questionnaire helps to identify level of need, range of support and associated funding required for achieving the defined outcomes. An analysis spreadsheet can then be used to analyse spend across needs for different children/young people, as well as predict future needs/trends for an individual child/young person. This provides local authorities with current allocation needs and future allocation needs analysis. This approach can be applied in schools in relation to the SEN notional budget.

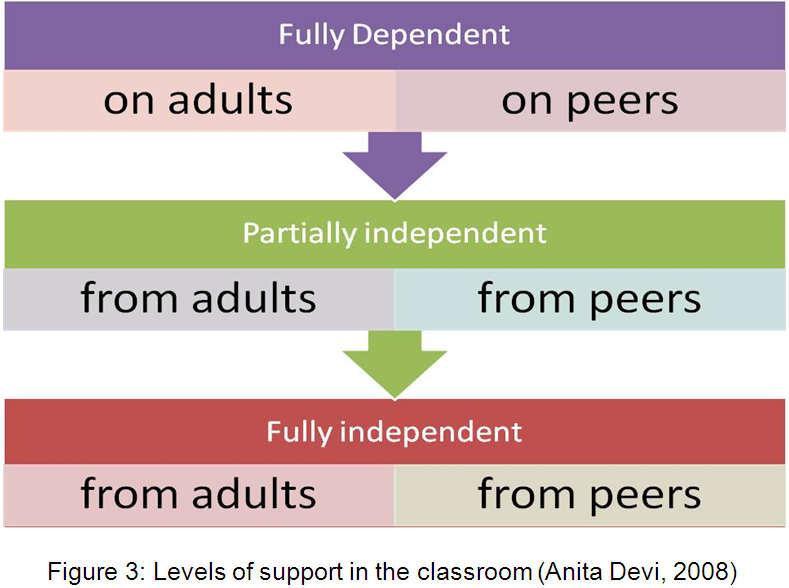

In 2008, I defined a similar model that could be applied in the classroom to determine the level of support given to a child or young people.

Applying the RAS principle in schools, figure 3 could be used to determine levels of support, a programme of provision; moving the child or young person to increasing levels of independence and against this where the funding is to be allocated from e.g. Wave 1 – quality first teaching, Wave 2, or Wave 3 (see article on commissioning in SEN ).

After the allocation of points in RAS, allocation tables are produced from analysis spreadsheets and these become visual, anonymous representations of how funding has been allocated. Once agreed, these should be published to demonstrate value for money (VfM) decision making and accountability. Again this approach could be applied to a setting’s notional SEN budget.

What are the success criteria for RAS?

The new systems and frameworks will take time to embed and SENCOs/leaders are encouraged to invest time in reading, discussing and disseminating information to staff/families in bite size chunks

In Control specifically states two success criteria of:

- Transparency – everyone understands what is happening, when and how decisions are reached.

- Participation – everyone who needs to take part can do so, and those who need support to participate are supported to do so.

From a school perspective, both of these principles are effective ways of evaluating your SEN systems and processes. However, further questions around funding streams could also be explored as we step into the final few months of implementation.

- What funding will be made available to form part of a potential personal budget?

- How will the local authority, schools forum and local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) meet their responsibilities to provide services to a wide and diverse population of children, young people and families whilst being clear when and how a potential personal budget will be made available?

- How and what information will be provided to families to enable them to make informed choices about funding and to decide whether they will request a personal budget?

- How will families access support to help them manage a personal budget as a direct payment?

A final thought...

The SEND reforms are still being trialled. The new systems and frameworks will take time to embed and SENCOs/leaders are encouraged to invest time in reading, discussing and disseminating information to staff/families in bite size chunks. The new world provides us with a real opportunity to learn from the past and develop a better tomorrow. Exciting times!

Further Reading

- Prabhakar, M. et al (2009) Individual budgets: Scoping Study. SQW

- Prabhakar, M. et al (2012) Individual budgets for disabled children, young people and their families. SQW

- Prabhakar, M. et al (2012) Individual budgets, evaluation of extended packages of support. SQW

- SEND Pathfinder Information packs

- Stobbs, P. (2013) School funding changes and children with SEN in mainstream schools. Council for Disabled Children

In previous articles I addressed SEN Commissioning in Schools and Outcomes-based Accountability (OBA).

Last Updated:

27 Feb 2014