- Latest NewsUp-to-date articles giving you information on best practice and policy changes.

- Model PoliciesA comprehensive set of templates for each statutory school policy and document.

- Skills AuditsEvaluate your skills and knowledge, identify gaps and determine training needs.

How retrieval practice can help pupils remember and understand

A cognitive psychologist explains why testing can help learning, and how teachers can use retrieval practice to boost their pupils' knowledge retention

Testing is often thought to oppose learning. Time spent quizzing pupils on their knowledge, the argument goes, takes away from time that could be spent acquiring it. What this ignores is the power of the testing effect: testing can help reinforce knowledge, as well as assess it.

Whenever I am planning a new course, I identify what the point of taking this course is, and what I want pupils to achieve by the end. I want them to gain knowledge, and I want them to understand what they have learned and be able to transfer it to situations outside of the classroom.

Testing can help reinforce knowledge, as well as assess it

To help my pupils do both these things, I give frequent tests and quizzes in all of my classes. I give these quizzes for two reasons: I want to help my pupils learn, and I want to teach them how to take control of their own learning and use learning methods that are effective when they study on their own. Evidence from cognitive science labs and research in the classroom suggests that quizzing can do both.1

Why do I love quizzing?

When pupils answer questions on tests or quizzes, they engage in retrieval practice. In other words, they actively bring information to mind in order to answer the questions. This act of bringing information to mind improves learning in a few different ways.

Here is how I capitalize on retrieval-based learning in my university setting.

I give my students a number of brief pop-quizzes for extra credit. At the beginning of random lectures, I present a few questions, and students write their answers in exam booklets. I make sure to ask broad questions, and require the students to describe and explain concepts taught previously.

For example, take auditory perception. I might ask students to describe how air pressure is turned into sound in the ear. They will need to explain what happens in the outer ear, middle ear, and inner ear. They will also need to explain how each part works together to create a signal for the brain. (See another example here).

The questions require a fair bit of writing, so I usually give the students around 10 minutes to answer the questions. I collect the booklets, and then call on students to answer the questions out loud. We talk about the answers, and I correct misunderstandings.

How do quizzes help pupils learn?

Quizzes have a number of benefits, including:

- improving retrieval of learning and ability to apply in different situations

- providing motivation

- diagnosing misconceptions or areas where further instruction is required.

Read on for further detail...

Engaging in retrieval practice via quizzing helps pupils learn in more than one way. First, practicing retrieval directly helps pupils learn. This happens even in the absence of feedback, or an opportunity to restudy the information.2 Bringing the information to mind literally causes the pupils to learn the information better. What’s more, bringing the information to mind improves pupils’ ability to apply the information in new situations.3

There are a lot of indirect benefits of giving pupils regular quizzes as well.1 For example, my university students know that they can only get extra credit from the quizzes if they are present and keeping up with the material. So, by providing random extra credit quizzes I’m hoping to motivate my pupils to come to lessons, to come prepared for lessons, and to pay attention during lessons.

Retrieval-based learning is not just for college students

Quizzes help pupils identify what they know and what they don’t know, giving them a better idea of how well they are grasping the material, and hopefully motivating them to study more and allocate their study time effectively. Normally I will give feedback immediately after the quiz to correct misconceptions. However, some research suggests that immediate feedback may not be necessary, so long as it’s given.4

Quizzes also give me an idea of how well the class as a whole grasps the concepts. If a couple of my students are struggling, I can reach out to them and encourage them to come to my office to ask questions individually. If many pupils are struggling this tells me that I need to do something different during lessons. I can rethink the way I am explaining something, or provide additional instruction in the classroom to make sure I am clearly presenting the points.

All of these benefits come from about 10 minutes at the beginning of the lesson. And -- the icing on the cake -- often pupils actually like doing these quizzes! Who could ask for more?

What about other methods of having pupils practice retrieval?

Research has shown time and again that practicing retrieval helps college students learn. My example above is just one way to implement retrieval practice in the classroom: multiple-choice questions, short-answer questions, and asking pupils to simply write everything they know from memory helps pupils learn!

Retrieval-based learning can extend beyond just quizzing as well. Pupils can create a concept map or another visual representation of material from memory.56 As long as they are bringing information to mind in absence of their notes or books, and they are successful at bringing the information to mind, they should benefit from retrieval practice!7

Does this apply to primary and secondary school pupils?

Retrieval-based learning is not just for college students.

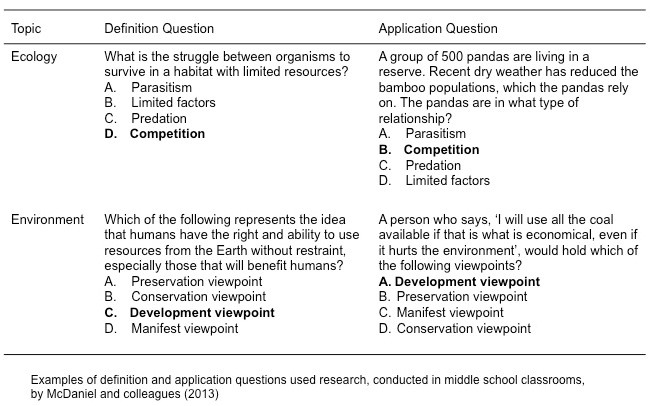

Research has shown that pupils from Year 7-9 benefit from taking frequent quizzes in their science classes throughout the semester.8 In this research, the pupils took three multiple-choice quizzes, during class, spaced out within the unit. The quizzes contained definition questions and questions requiring them to apply concepts to new situations.

The table below shows example questions from their research.

On the exam at the end of the unit, quizzing greatly improved performance compared to when the pupils did not take the quizzes.

Most importantly, the pupils were better able to remember definitions from the unit, and were better able to answer new questions requiring the pupils to apply the concepts in new situations. Adding three multiple-choice quizzes in a middle-school science class improved pupils’ ability to understand and apply the concepts!

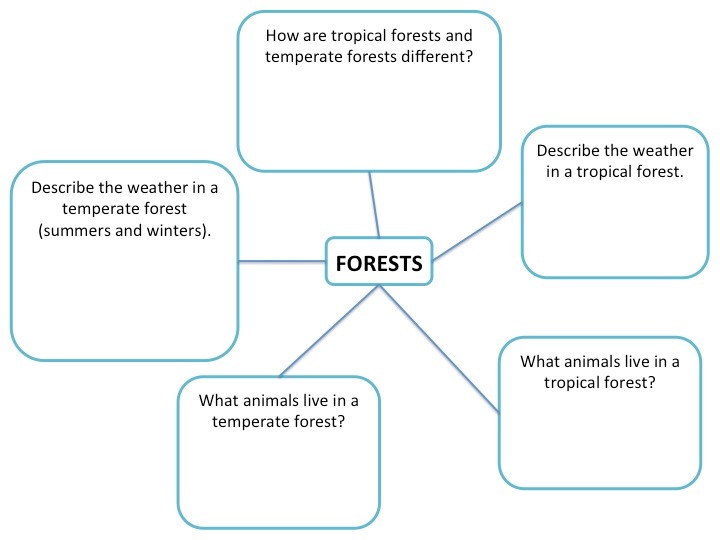

Retrieval-based learning has been effective with pupils even as young as years 4 and 5.6 Pupils at this age have a hard time writing out everything they know (i.e. free recall). However, guided activities that require pupils to practice retrieval help them learn.

In this research, teachers gave pupils question concept maps (like the one below). Pupils had to fill in the missing information by answering the questions. This helped them learn the concepts better than passively reading the material.

Teachers are often looking for ways to help their pupils learn basic information about a topic and to better understand the concepts and be able to apply them in new situations.

For both of these goals, for college students to pupils as young as Year 4, engaging pupils with retrieval practice is effective.

References

You can find many of these research papers, and others related to retrieval practice, on these lab websites.

- The Cognition and Learning Lab (Jeffrey Karpicke at Purdue).

- The Marsh Lab (Beth Marsh at Duke).

- The Memory Lab (Henry Roediger at Washington University in St. Louis).

Studies cited

- Roediger, H. L., Putnam, A. L., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Ten benefits of testing and their applications to educational practice. Psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education (pp. 1-36). Oxford: Elsevier.

- Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17, 249-255.

- Smith, M. A., Blunt, J. R., Whiffen, J. W., & Karpicke, J. D. (in press). Does providing prompts during retrieval practice improve learning? Applied Cognitive Psychology.

- Mullet, H. G., Butler, A. C., Berdin, B., von Borries, R., & Marsh, E. J. (2014). Delaying feedback promotes transfer of knowledge despite student preferences to receive feedback immediately. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 222-229.

- Blunt, J. R., & Karpicke, J. D. (2014). Learning with retrieval-based concept mapping. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 849-858.

- Karpicke, J. D., Blunt, J. D., Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, S. S. (2014). Retrieval-based learning: The need for guided retrieval in elementary school children. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 198-206.

- Smith, M. A., & Karpicke, J. D. (2014). Retrieval practice with short-answer, multiple-choice, and hybrid tests. Memory, 22, 784-802.

- McDaniel, M. A., Thomas, R. C., Agarwal, P. K., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. (2013). Quizzing in middle-school science: Successful transfer performance on classroom exams. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27, 360-372.

Last Updated:

09 Apr 2018